The number of verified signatures by William Shakespeare might just increase this week. A group of undergaduate researchers at the University of Mississippi led by Professor Gregory Heyworth recently performed an incredibly fascinating spectrum analysis of the so-called Lambarde signature of William Shakespeare at the Folger Library. This signature, unique in comparison to the other six known Shakespearean autographs, could actually give us a glimpse, however small, of the poet from Stratford’s personal library. While we may never know if this signature does indeed belong to Shakespeare, the results from these images could go a long way towards at least convincing scholars that it isn’t a fake.

Ars Technica spoke with Professor Heyworth earlier this week to learn a bit more about this project:

Heyworth takes pains to state in no uncertain terms that it may never be possible to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that it is by Shakespeare. However, if the spectral fingerprinting they did on this signature is consistent across other known signatures, it would come very close to definitive proof. If, however, it is consistent with known forgeries, that too would be a near-definitive judgment.

“The so-called Lambarde signature on the Archaionomia that we imaged was suspected by its first owner in the 1940s of having been by famed 18th century forger William Henry Ireland. […] We know that Ireland used a special formulation of ink combined with acid and paper-marbling fluid for all his forgeries. Inks all refract light differently, according to their chemical composition. Multispectral imaging, then, combined with spectral analysis of particular spots, yields data indicating the unique refraction of light at various wavelengths. I call this a multispectral fingerprint, although it is not as exact.”

I’m not a Shakespeare scholar myself, but I have to admit that I’m fascinated by the possible implications of Shakespeare’s signature in a fairly obscure legal text. Andrew Henning, the Ole Miss senior who spearheaded the project, also speaking with Ars Technica argues for a possible interpretation:

“For one, […] it suggests that, at the very least, Shakespeare possessed and was actively reading legal texts. Some might even argue that it draws a strong line indicating that Shakespeare was in some way involved in the English legal system.”

And this may certainly be the case. Many of Shakespeare’s plays involve legal issues, but why would he have chosen this text? Looking for an expert on the subject, I spoke with MARCO director and Shakespeare scholar Heather Hirschfeld to get her take on this story. Dr. Hirschfeld, while pointing out that the signature does seem a bit “off” in comparison to some of the others, did remind me of the importance of not only contemporary, but early law codes to Shakespeare and his contemporary playwrights. And it is the early nature of Lambarde’s book that chiefly concerns me.

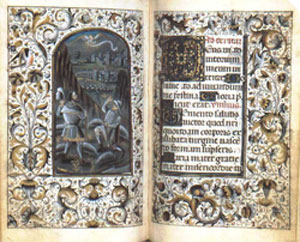

Ink showing through from recto to verso side of leaf (image has been reversed left to right). Photo from The Folger Library

I do quite a bit of work with the English vernacular antiquarians of the Elizabethan age, so I’m actually a bit more comfortable these days with the work of Lambarde and others like him than Shakespeare, so I have absolutely no understanding of why Shakespeare would own and even sign (perhaps annotate too?) a dual-language (that is, Anglo-Saxon English and Latin) edition of the laws of Cnut and various other pre-Conquest kings. Not only is it questionable just how thorough Shakespeare’s Latin was, it is almost never discussed whether or not he knew even a few words of Old English (and why would it be?). Yet here is a book, ostensibly his, which was printed both to showcase the new Anglo-Saxon typefaces developed by Matthew Parker and John Day and to demonstrate the ancient models of Saxon law codes to a new audience. While Lambarde was the first to do this, he certainly wasn’t the only antiquarian to take an interest in finding Anglo-Saxon legal precedents and presenting them to the public. Symonds D’Ewes, for one, enthralled other members of parliament with his readings of various laws of Alfred and Aethelred, in the original language, to whomever would listen.

But what would Shakespeare be doing with this book? Honestly, it seems that if this research rules out the more likely forgeries, there will be more questions raised than answers. And that might just be the mark of really great scholarship. So, many thanks to both Ole Miss and the Folger Library for putting this technology to some fascinating uses.

Source: Ole Miss Z!NG via The Collation and Ars Technica